The Australian economy's key decision-makers talk about China a lot. In virtually every monetary policy statement, for example, Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor Michelle Bullock discusses the growth outlook for the Chinese economy, while it's never far from Treasurer Jim Chalmers' lips either. But why?

Why does the Chinese economy matter to Australia?

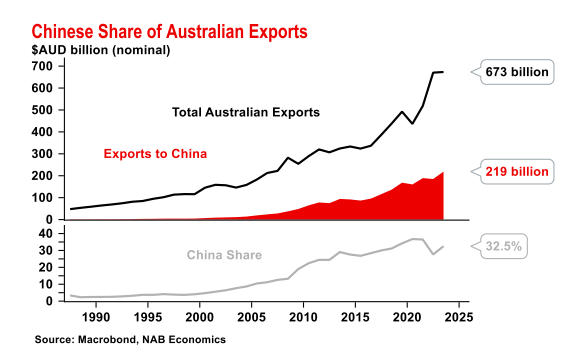

The Australian economy is closely tied to China because it buys so many of our goods and services. Australia exports far more to China than it imports. This is a bit unusual since most countries have a trade deficit with China - at the time of writing its overall trade surplus is nearly an astonishing $1 trillion.

In 2023, Australia sold roughly $219 billion worth of goods to China according to government figures. With Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at about $2.67 trillion, exports to China comprised approximately 8.2% of Australia's GDP.

As China has rapidly industrialised over the past couple of decades, it has ramped up spending on Australian goods significantly, majorly boosting our economy. The biggest contributor to the mining boom over the decade to 2012 was increased demand from China for materials like iron ore, used to make steel.

The RBA estimates that the mining boom boosted real per capita household incomes (adjusted for inflation) by 13%, reduced unemployment by 1.25%, and raised real wages by 6%.

What do we sell?

The biggest reason for the trade surplus is that Australia supplies many of the raw materials China needs. In 2023, China spent about $116 billion on iron ore from Australia - 53% of exports to China, 17% of the overall total exports according to NAB. That means more than 4% of our entire GDP just comes from selling iron ore to China. LNG, with $20 billion worth of exports in 2023, and coal ($9 billion) are the other major industrial goods China buys.

It isn't just industrial commodities - China also spent $15 billion on services like international student tuition fees and tourism. Agricultural products like meat, wool, and wheat made up a further $11.5 billion, with about 80% of Australia's wool exports going to China.

At the end of the day though, those raw materials are the major reason Australia is sensitive to Chinese growth.

Is Australia over exposed to mining?

The Harvard Economy Complexity Index ranks nations by the 'current state of productive knowledge.' It measures the variety of products a country exports and how difficult it is to make those products. For example, Japan has been the most complex economy since 2000. Think about Toyota, Samsung, Hitachi, Nintendo, etc. - there's a huge range of different stuff coming out of Japan that takes serious expertise to produce.

Australia, on the other hand, most recently ranked 93rd. Uganda, Honduras, Kazakhstan, Cambodia, and Laos, among many other developing nations, all ranked higher. This is despite Australia ranking near the top ten nations for GDP and GDP per capita. Mining, and to a lesser extent farming , does much of the heavy lifting. For the moment this isn't a huge issue, but like an investor with all their eggs in one basket, it means Australia is highly dependent on the mining sector and commodity prices.

How bad is a Chinese slowdown for Australia?

Prolonged weak growth in China could lead to decreased demand for Australian exports and lower commodity prices.

Lower export volumes

If, for example, Chinese developers aren't building as many skyscrapers, steel manufacturers might end up buying less iron ore from Australia.

Senior NAB economists Gerard Burg and Brody Viney call a slowdown in Chinese construction a "downside risk" to export volumes, but said this wasn't a certainty.

"The impact would depend on the extent of the shift in demand and Australian producer's position in the cost curve," the pair wrote.

"Whether the volume of Australia-China iron ore trade would be affected by a reduction in Chinese steel consumption would depend on….whether there are offsetting increases in steel demand from other developing countries that could be export destinations for Chinese steel".

Lower commodity prices

The indirect impacts of a Chinese slowdown may have larger ramifications. The Chinese industrial sector is a monster that's probably the world's biggest consumer of raw materials. If demand slows, it would likely drive down commodity prices. Australia might then have to sell its iron ore, coal, and LNG, whether to China or elsewhere, for less. This would hurt mining profits, which could reduce government revenues. Iron ore and coal royalties are a big source of revenue for the Western Australia and Queensland state governments respectively, while the Federal Government also collects a healthy amount of taxes from mining companies.

Burg and Viney said lower commodity prices would be the main impact of any slowing in China's growth.

"Weaker commodity prices would reduce the profits of exports and by extension the household wealth of their shareholders and the revenue of governments."

China and Australia in 2025

Economically at least, a prosperous China is good news for Australia. Heading into 2025 however, the Chinese economy faces a couple of major headwinds.

The property sector, long a major growth driver, is undergoing a significant downturn. Early this year, the giant developer Evergrande went into liquidation.

Low domestic demand is another issue. China's unprecedented economic development over the past few decades has mostly been driven by investment and exports. Local consumption - Chinese people buying Chinese goods and services - makes up just 50% of their GDP compared to 75% globally, according to the World Bank. Burg and Viney say that since COVID-19, several factors have caused Chinese households to tighten the purse strings further.

"A lack of fiscal support for households [during the pandemic], the fallout from the severe property downturn and regulatory crackdowns on private sector firms have negatively impacted domestic growth," they wrote.

The Chinese Leadership announced several fiscal stimulus measures at the National People's Congress aimed to address this, and things have picked up. ANZ forecasts suggest China will end 2024 with annual GDP growth of 4.9%, on target, but its economists say it's "too early" to determine whether this will lead to a sustainable recovery.

What would Trump's tariffs on China mean for Australia?

Heading into 2025, most chat about the Chinese economy includes what Donald Trump calls "the most beautiful word in the dictionary". The incoming US president says he plans to implements tariffs across the board on incoming exports, and is threatening to impose tariffs of up to 100% on Chinese goods.

A tariff is basically a tax on imports to a country. Say a Chinese company wants to sell an excavator valued at $100,000 - a 100% tariff would mean it has to pay the US government $100,000 to do so.

The likely consequence of this is reduced Chinese exports to the US, which could have a flow-on effect to demand for materials. If they are selling fewer excavators, for example, manufacturers might not use as much steel, reducing the need for iron ore.

Navigating the ripple effects: China's economic influence on Australia's future

At the end of the day, China's economic performance carries a lot of weight for Australia. With such a large portion of our economy tied to the demand for raw materials and services, any downturn in China will have a knock-on effect here. The immediate risks, like falling commodity prices and reduced export volumes, are clear enough. But it's worth remembering that the relationship between Australia and China isn't fixed-things are always shifting. As China faces new challenges, Australia will likely need to look at other markets and find ways to lessen its reliance on one economy.

Looking ahead to 2025, Australia's economic outlook will undoubtedly remain linked to China's fortunes. Whether that means adjusting to slower growth or seizing new opportunities, one thing is certain: keeping an eye on China's economy will be essential.